CDMX: Lights, camera, death

I can’t remember what came first - my desire to experience Día de los Muertos in Mexico, or the release of Spectre.

But both collided in Mexico City one November.

CDMX now draws more than a million visitors to its Day of the Dead parade, something that didn’t actually exist until after the movie. The opening of Spectre (2015) shows James Bond weaving through a surreal street celebration of skeleton floats, dancers, and face-painted crowds.

In a true case of life imitates art, or cinema influences civic policy, CDMX launched its first official parade in 2016. Since then, it’s grown into a high-production event with floats, costumes, music, and predictable criticism: that it commercializes and appropriates a sacred tradition, that it dilutes meaning in favor of spectacle, that it’s mostly for tourists. All valid points. Still, I booked my ticket to CDMX and rewatched the Spectre scene, plus all behind-the-scenes footage I could find, in preparation.

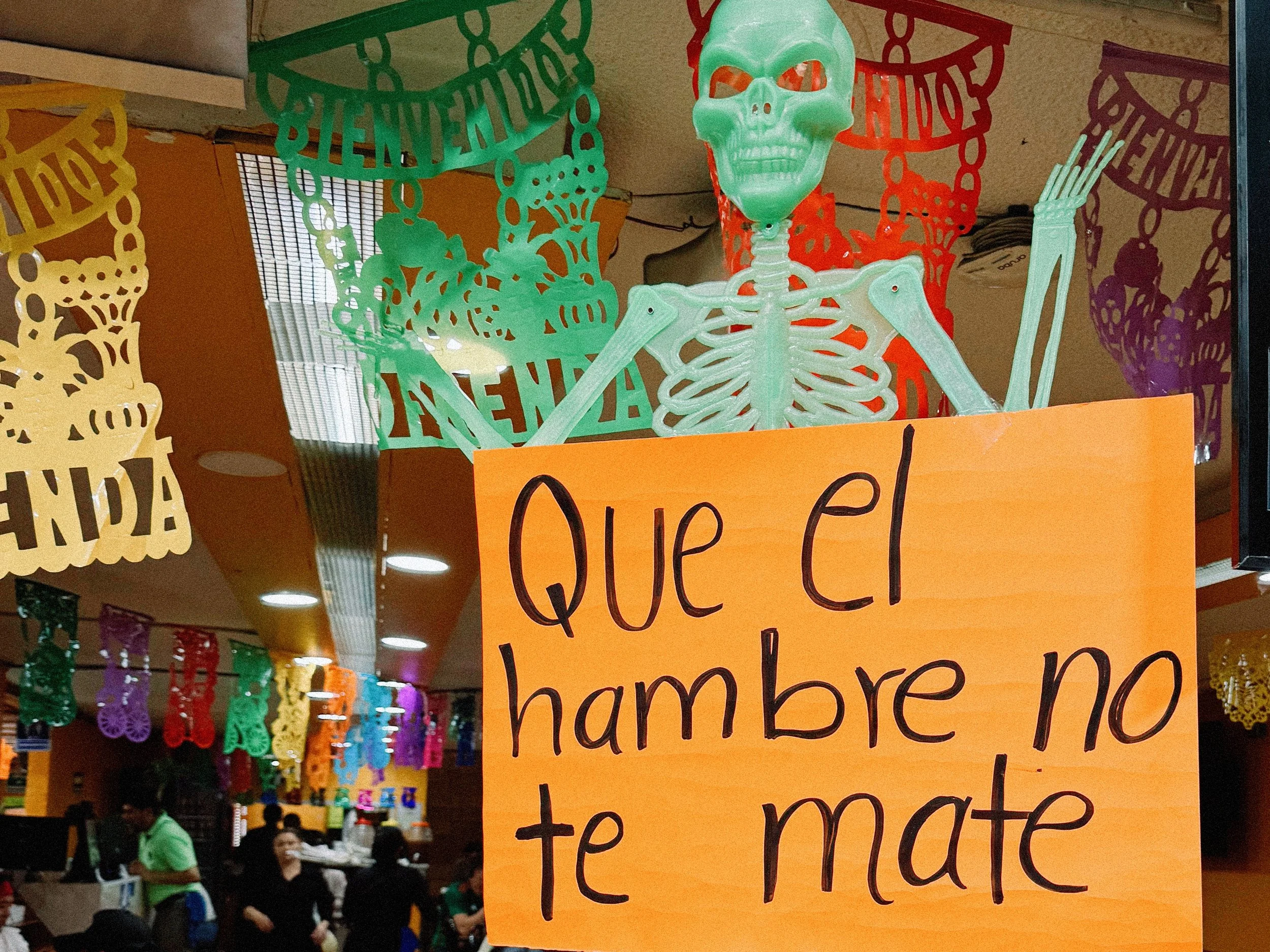

When I arrived a few days before the scheduled parade, the celebrations was already in semi-full swing. The central square—Zócalo—had turned into a state-sanctioned altar: a massive ofrenda surrounded by skeleton statues, marigold arches, and light installations that hovered between traditional and contemporary. Crowds moved through in face paint and floral crowns. Street vendors sold tamales and corn next to booths offering neon halos, face painting, and photo ops with volunteers in traditional get-ups. It walked the line between authenticity and performance.

The parade itself is less a spiritual event and more a pageant. Local artists and businesses build floats. Marching bands loop past in face paint. Tourists line the barricades with phones held high. There’s a fair critique to be made about the commodification of the tradition. But even surrounded by LED devil horns and churro carts, it’s hard to not feel the spirit of the tradition, which is to accept and celebrate death as an integral part of life.

I lost a loved one at a young age, so I’ve never had the luxury of thinking about death in abstract terms. In my culture, death is treated with solemnity and restraint. It’s marked as a tragedy to mourn quietly and not revisit annually or even often. Rituals exist, but they’re designed to process the loss, not celebrate the life. There’s a prescribed seriousness and heaviness to it, which often makes it harder to remember the departed with much joy..

Día de los Muertos treats death less like a singular tragedy and more like a shared, ongoing relationship. It acknowledges absence without flattening it solely into grief. It invites the dead back for a visit, and builds something beautiful and fun for their arrival. It made me wonder: what would people leave at my altar? Can I make requests? Is there a registry? As someone who often lives with the fear of dying, or someone I love dying, it was a refreshing and liberating change to see a different way to relate to the concept of death.

In that sense, it’s impressive that a film could lead to a real-life event capable of inspiring these kinds of experiences, reflections, and internal monologues on such a scale. Of course, the traditions predate the film by centuries, but part of the power of film and art is their ability to connect people to cultures, places, and histories they might never have otherwise encountered. Or to motivate them to experience and learn about something firsthand, even if the initial impulse was just to feel like 007.

The fact that the Spectre scene was shot on location with 1,500 real extras in costume, handmade props, elaborate sets, and makeup by local artists also means something. It may have been imagined by a British director and funded by a Hollywood studio, but part of what made it spectacular was the work of people in Mexico City. The visual power of the scene came in equal parts from concept and execution - the physical labor, cultural specificity, and artistry that went into building it.

I can’t be writing this in 2025 and not wonder: would any of this have happened if Sam Mendes had access to generative AI at the time? If he could have simply prompted the scene into existence just a highly detailed output rendered from a few well-written instructions, would it have had the same impact? Would the city have felt compelled to recreate it? Would I have felt compelled to go?

Of course, there are plenty of examples of fictional or animated worlds that later inspired real-life versions. Art doesn’t always have to be physical to be influential. But in this case, I think the fact that the scene was made in the real world played a major role in what followed.

I’m pro technological advancement and I believe AI will open up new forms of creativity. But I also think there will always be a place and a case for making art in the real world. After experiencing Día de los Muertos in CDMX, it’s hard not to feel that physical presence carries a kind of meaning and impact that can’t be fully replicated virtually.